At Invetech, we believe that good design leads to more successful products and improved business growth. With ever increasing competitive pressures, it is no longer acceptable for a new product to simply work from a functional perspective; it must create a rewarding user experience. However, when looking at new product development processes, there can be a tendency to overlook design, which seems a missed opportunity for increasing market share.

At Invetech, we believe that good design leads to more successful products and improved business growth. With ever increasing competitive pressures, it is no longer acceptable for a new product to simply work from a functional perspective; it must create a rewarding user experience. However, when looking at new product development processes, there can be a tendency to overlook design, which seems a missed opportunity for increasing market share.

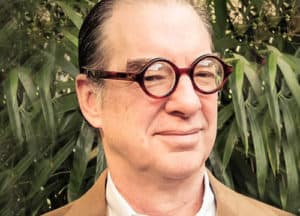

Enter Steve Wilcox, a pioneer in user-driven product design. Steve is the founder of Design Science, a firm specializing in providing insight, research and UI design services to drive organic growth for companies developing new products. Steve has published more than 65 articles and book chapters on the topic of design and serves on the advisory board of the Carnegie Mellon University School of Design. Steve is particularly well known in the healthcare community for his book, Designing Useability into Medical Products, co-authored with Michael Wiklund.

Today, I am pleased to be catching up with Steve as part of Invetech’s series on growth, and to discuss how good design can fuel market success when developing new products.

Colin: Steve, good morning, thank you for your time.

Steve: Good morning.

Colin: Steve, I would like to start by asking you to clarify some of the language used in this sphere: Human factors, design, usability engineering—are these things all the same? And what is the best way for lay folk to think about these terms?

Steve: Let me start by defining Human factors. The discipline of Human factors is the application of knowledge of human beings to the design process. It’s kind of an adjunct profession to designers. We Human factors folk typically partner with product designers and developers.

Human factors is generally defined as the application of knowledge about human beings to design, and there are two parts to that. One is the cognitive part: knowledge about thinking and memory, applying information to make the product easy to learn and easy to remember. The other side is physical human factors: studying the shape and size of the body, as well as strength and movement, working on problems like how to make controls easy to use.

That is the body of knowledge, but like many disciplines it’s also a methodology. So one method involves finding information—from this body of knowledge—about human beings that applies to design. Setting that aside, the two most important methods are observational research—sometimes called ethnographic research—where we go out into the field and study how things are used and find opportunities for improvement. The other is usability testing, where we take a prototype, stick it in front of a person, have them use it, and see what kinds of mistakes they make in order for us to improve the product.

That’s human factors, and that’s the term that is used for this discipline most often in the U.S. Some other terms that are commonly used are usability engineering and ergonomics. Ergonomics is the British term, so it’s a synonym of human factors but is more commonly used in the U.K.; we tend to use the term Human factors in the U.S.

Colin: It seems to me that the topic of human factors—as you say sometimes called ergonomics—is certainly one that is getting a lot more airtime with management these days. What is your perspective on the underlying drivers of that?

Steve: Well, the trajectory I’ve been watching unfold for the last 30 years as I’ve been doing this work is that a new product category appears that’s largely driven by some kind of new technology, or some fundamentally new idea that is protected by some kind of intellectual property. Then the battle for market share is based upon the technology and the new product doesn’t really have competitors. So regardless of usability, the product is still sold. Then the technology begins to mature, and all of a sudden, usability becomes one of the key methods of making a successful product. The way one product differentiates itself from another is Ergonomics.